The First Animals

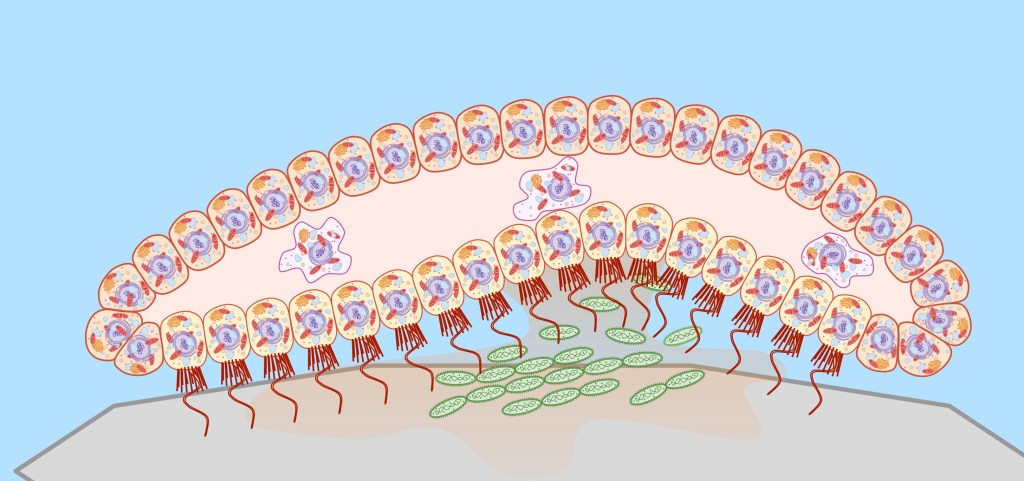

The story of the first animals begins with a particular kind of protist: the choanoflagellate.

This is a choanoflagellate.

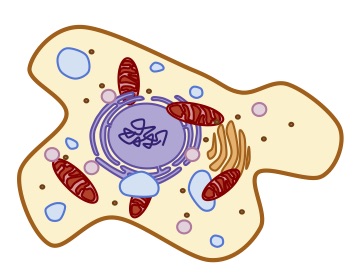

But sometimes she looks like this

And other times even like this

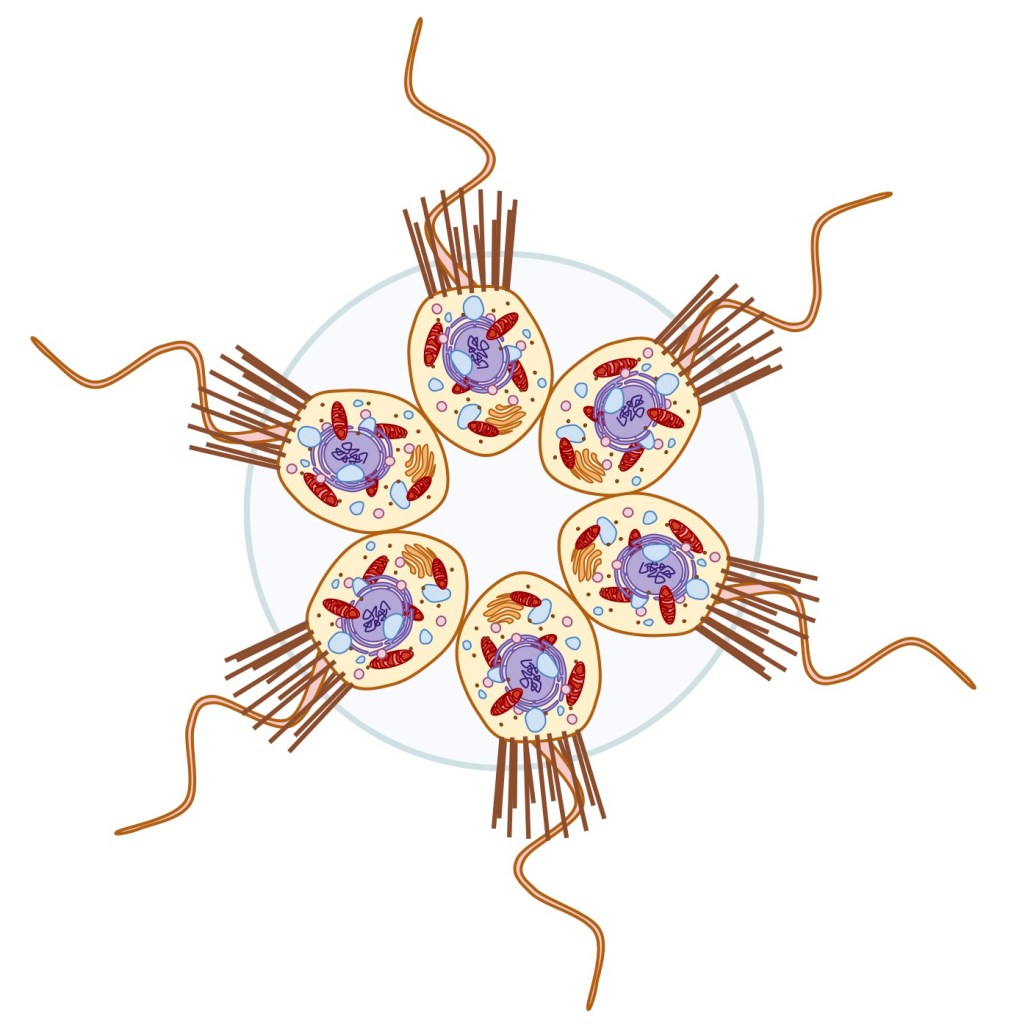

Like all eukaryotes, she is a shapeshifter at her core, and her genome remembers all the forms she has ever taken. As choanoflagellate colonies become more complex and stumble into multicellularity, they begin to incorporate these shapeshifting forms to do different tasks. Some cells specialize to become the structure of the organism, each one becoming a dutiful brick in a vast, impenetrable castle. Others specialize in collecting bacterial food and moving the organism by using flagella to create currents of water. Others detach entirely from the structure of the organism and take amoeboid forms that patrol the interior, looking for foreign invaders that may do it harm. These choanoflagellate colonies experiment with different architectures, giving rise to a diversity of early animals.

One of the first animals to appear (and still exists today) is a humble creature called a placozoon. To us it looks like a meaningless speck, a mere flake less than 2 millimeters long. In reality, it is one of the world’s first animal super predators. It is a flat colony made of about five different kinds of cells which has a protective back and a busy bottom covered in little flagella that allow it to creep its way along the ocean floor. When it encounters its tiny prey, it traps the smaller beings underneath its belly and spits acid and enzymes to digest them outside its body before absorbing their juices as food.

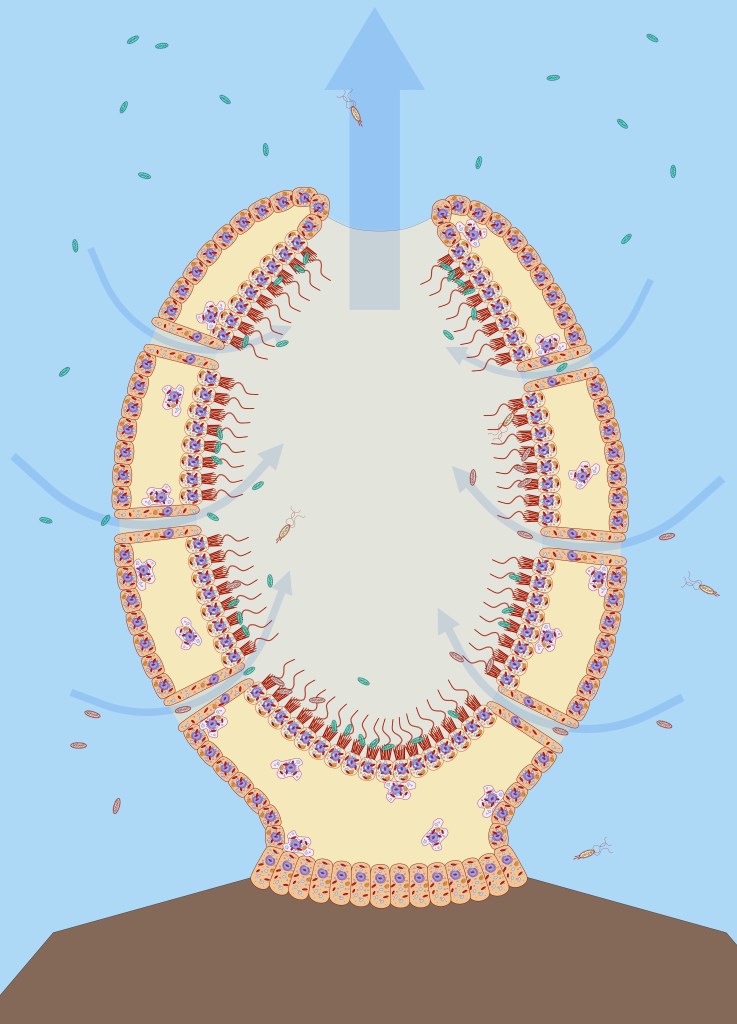

In addition to tiny ocean hunters, animals also experiment with much larger, stationary colonies. Many single-celled creatures have known for billions of years that the best way to find a meal in the ocean is often not to run around hunting but to stay put. Instead of swimming, they hold tight to something and filter water for yummy morsels drifting by. The sea sponges take this strategy to new heights by creating enormous colonies of millions of cells funneling and filtering quantities of water unimaginable to their single celled ancestors.

The sea sponges then and today create a unique skeletal structure out of bone-like material or stuff that resembles fiberglass. These hard, little, spiky pieces easily fossilize, leaving traces that make the sea sponges the first recognizable animal in the fossil record. DNA studies have found that they and the placozoa are amongst the very oldest branches on the animal tree of life.

Squishy Creatures

As life continues to explore, new, more intricate animals arise. A key innovation for these increasingly large and complicated colonies is a way for one side of the organism to quickly communicate with the other. They develop a network of long, branching cells that coordinate signals across the colony like telephone wires, thus giving rise to the first nervous systems.

Another key development is the invention of muscles. Cells changing their shape to move around is an ancient ability, but, for the first time, animals create special cells with the specific job of pulling. Now, a few mighty cells can move thousands of their sisters, changing the shape of the whole colony. With these two innovations of neurons and muscles, motions can be coordinated across the animal to propel the largest ever moving organisms through the ocean. They are like battlecruisers swimming alongside millions of their single cellular compatriots.

With these new innovations, life tries out a diversity of body plans. There are colorful anemones, wriggling worms, slippery slugs, and feathery filter feeders. New creatures peacefully swim and crawl all over the oceans in bizarre shapes that the world has never seen before and many it will never see again.

The Cambrian Explosion

With this new diversity of multicellular creatures, the complexity of life skyrockets. The period of soft, slow, peaceful animals filtering the ocean for plankton ends as multi-cellular creatures discover not only can they eat microscopic life but also one another. An arms race ensues as both hunter and prey develop weapons and defenses. Some animals figure out how to swim quickly, many develop hard shells, and others learn to burrow into the muck on the seafloor to escape from the increasingly scary hunters above.

The burrows and shells of this era fossilize easily, leaving behind a rich fossil record for the very first time. So stark is the difference in fossils that, if you were a paleontologist two hundred years ago, you’d likely think that life suddenly sprang into existence already in a diversity of multicellular forms!

Strange swimming arthropods patrol the waters. They’re not much longer than your forearm, but they are giants compared to the the other animals of the era. They have various specialized appendages like sharp pincers for plucking prey out of the mud or fine combs for filtering food from the open ocean. Sea lilies sway in the current, catching food with their feathery arms while snails scavenge at their roots. Clam-like creatures cluster onto rocks and burrow into sand. Trilobites become one of the most successful animals on the planet and will continue to scurry around for hundreds of millions of years.

Fish and Co.

A particular family of ocean animals develop a body plan streamlined for speed. They find that they can move the fastest if they organize their muscles around a flexible central rod and use them to wiggle their long, skinny bodies through the water. To top it all off, they connect their neurons to a central control unit at the tip of the rod that orchestrates the timing of the muscles with signals coming in from their simple eyes and sensitive smellers. This bundle of neurons gives rise to the brain, and these sleek swimmers become the first fish.

The fish become some of the fastest animals in sea, exploring every niche they can. They haven’t yet figured out how to make jaws, so, instead, the predators amongst them develop a muscular mouth hole with many inwards pointing teeth allowing them to catch their slippery prey.

The teeth of a particular jawless eel-like fish called a conodont liter the fossil record for hundreds of millions of years. The shape of these teeth change with conodonts’ evolution, so rock layers with the same shaped fossil teeth must be the same age. Thus, finding a single distinctly shaped fossil tooth allows us date rocks today.

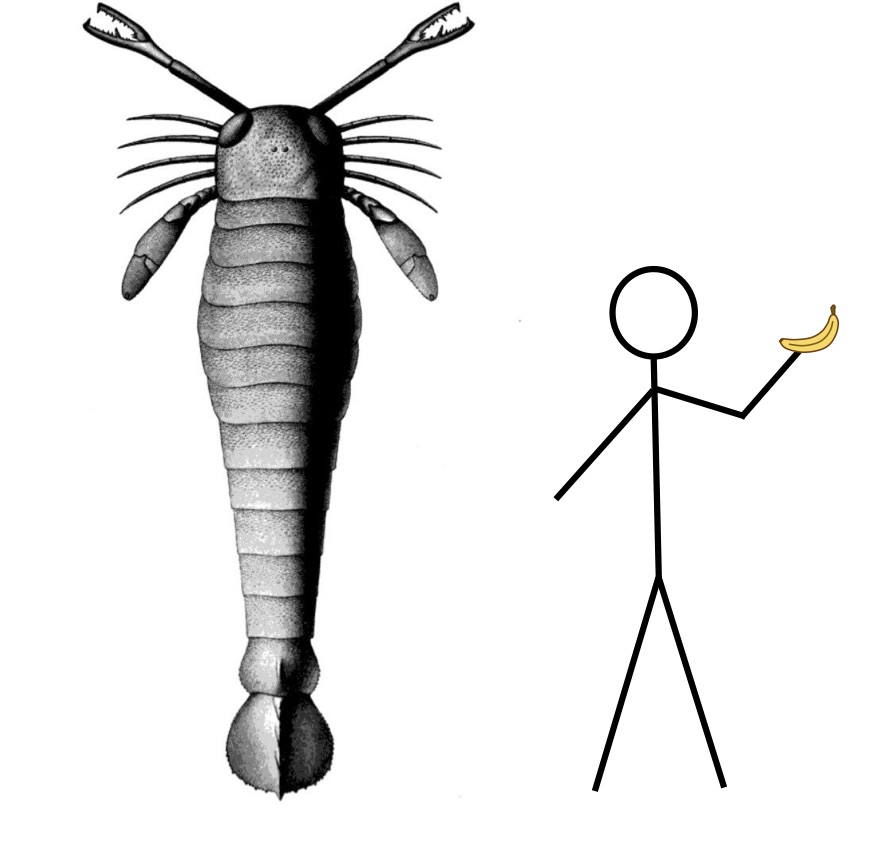

The fish are not the only innovators during this time. The oceans become increasingly full of other strange and terrifying creatures, among which is the giant sea scorpion.

human with banana for scale

Some fish, now being hunted by sea scorpions, squids, and bigger fish, repurpose the material in their teeth to make a light, flexible mail of scales. Some among them find that it’s better to trade some of their speed for additional protection and, instead, construct boney exoskeletal suits of plate armor. This strategy, pioneered by the arthropods and mollusks before them, makes it nearly impossible for crustaceans’ claws to grab hold.

These experiments with bone plates lead a lineage of fish to develop the first bone jaws which provide them with a reenforced tool for biting and grasping. This new tool is such an advantage that the jawed vertebrates diversify into many different forms, experiencing a glorious age of fishes. Some of them still bearing armor grow to be truly voracious predators. Others lose their plate armor in favor of speed, and give rise to the first small sharks.

Some continue the bone experiments and find that mineralizing their cartilage skeletons into bone brings different advantages. These fish take various shapes and experiment with new kinds of jaws and fins.

Keep your eye on this last group for they are destined for great things. One of them happens to be your very great grandmother!

Plants on Land

For the billions of years that the ocean was developing, the land was also slowly and subtly evolving. The vast continents of rocks and sand that arose from the ocean were initially inhabited only by brave bacteria. For eons they existed as little more than a dusting on the rocks and in between the grains of sand, slowly altering the dirt into soil. As cyanobacteria and other photosynthetic prokaryotes ventured onto land, some made large, gelatinous colonies that shriveled and desiccated under the sun, only to swell up again when the rains came. The land existed like this, only populated by rock and ooze for billions of years more.

a terrestrial filamentous cyanobacteria colony

When the multicellular eukaryotes appeared, the cleverest of shapeshifters among them made their way onto land. These were fungi, multicellular beings that forwent organized bodies for a branching, net-like structure. They specialized in living in the soil, spreading through it and becoming a part of it, like the veins and capillaries in your body. The clever fungi formed all sorts of relationships with the trillions of bacteria around them. They acted more as a merchant than a conquerer, striving to find situations where they could leverage their special abilities to benefit those around them in return for some sort of payment.

One kind of fungus came to strike a deal with the cyanobacteria. The fungus agreed to use its filamentous body to build a structure to protect the cyanobacteria, and the bacteria agreed to use their photosynthesis to feed the fungus. The unbeatable partnership gave rise to lichen, which spread everywhere on land. Many took up residence in the wettest environments. Others were thin, crusty, and austere, living on the highest mountain tops and the driest deserts. These fruitful ecosystems of bacteria, fungus, and lichens created the first great terrestrial gardens, turning huge expanses of barren land into pale, alien, grey-green tundra.

The order here of the evolution of fungus, lichen, and plants is actually quite unclear from what we know from the fossil record, so I’ve told it in a way that makes sense to me. The bead marks when there is clear fossil evidence of plant spores.

Eventually, the algae, eukaryotes with chloroplasts already packaged inside, also venture onto land. They give rise to the first simple plants, clinging to moist rocks like liverworts.

Next come the more complicated mosses. They spread out onto the land, turning the humid regions of the countryside into soft hills and valleys of bright green as far as the eye can see.

Imagine standing on world where mosses grew everywhere mosses could grow. It was a fluffy green wonderland for everything to follow.

Many kinds of bugs follow the plants right out of the water. With hard exoskeletal shells already suited for bearing their weight out of water, the bugs only have to make a few changes to their breathing apparatuses to live on land. As they learn to graze on the plants, this new mossy tundra becomes a great, green paradise for the crawling critters, full of food and void of predators.

The paradise does not last, of course, as bug predators like scorpions and spiders crawl out of the water after their prey. Now, with predator and prey again locked in their eternal dance, all of the crawling beasts continue to evolve with the rhythm of this new terrestrial world. One family of bugs even learns how to fly, the very first animals to do so. They become the insects, and their wings carry them to the far corners of the globe.

Amphibians

Some of the fish now living in the ferocious, shark-filled ocean discover these lands of tasty plants and plump bugs. They, too, figure out how to venture out from the water, turning sacs that were first used for buoyancy and later for breathing air in oxygen-poor waters into proper lungs. As these first adventurous fish make their way onto the land, they go from being the small fry in the ocean to the biggest animal around. With nothing to eat them, these small giants clumsily crawl and flop through low foliage, hunting millipedes and munching on plants without a care in the world.

Amongst the first land-fish[11]

Over time these amphibians diversify to many shapes and sizes, and the amphibians’ period of peace quickly ends as some of the larger land creatures specialize in eating the smaller ones. Some even grow to be the size of crocodiles and live similar lifestyles of lazing around, waiting to ambush their prey in swamps. Others find their legs and venture far onto the land, but they remain bound to water, always returning to lay their eggs.

a later amphibian[6]

Forests

As the land dwelling creatures adapt and become more fierce, the land dwelling plants, in their own way, do the same. At first, just being able to stake a claim on a patch of soil was all it took for a plant to be successful. However, as more plants begin to populate limited real estate, they too start to compete for their most important resource: sunlight. They resort to crowding each other out, growing over one another to win access to the light. This race towards the sun results in plants getting taller and taller, becoming a few feet high like ferns, then taller still to be bushes, and finally growing to tower over the landscape as the first trees.

an ancient tree[12]

Soon, great forests of bizarre looking trees expand across the land, becoming huge rainforests, whose dank depths are full of strange, slimy, and scaly critters.

As the oxygen content of the atmosphere continues to rise (about 60% more than today’s level), bugs and other creatures whose sizes are limited by how oxygen moves through their body grow to enormous size. Darting through the skies, there are dragonflies the size of hawks, and likely as agile of hunters. Some millipedes scrounging about the forest floor grow to be larger than humans.

The forest thrives as its trees reach ever higher towards the sun, and its vegetarian critters feed off of the rich plant life. Some trees develop protection from these critters: woody tissues so hard they are nearly impossible for the bugs to eat. In fact, the wood is so hard that even the fungi and bacteria can’t yet digest it. This causes the wood to pile up on the forest floor and slowly sink into the swampy soil.

Eventually, all this buried biomass fossilizes to become coal. We still burn the coal from this time to produce electricity, perhaps even to power the screen you’re reading this on.

The trees cover continents in great blankets of green as the continents themselves continue their slow drift across the Earth. The rainforests, supplied with water by winds from the ocean, begin to falter as the sea between two great continents shrinks. As they collide in slow motion, land that was once coastline is thrust up into enormous mountains the size of the Himalaya (the remnants of which we now call the Appalachians). The trees and all their denizens find themselves locked far away from the ocean, and most of the land turns to desert in the middle of the vast supercontinent Pangea.

Permian & The World of Lizards

The desertification and collapse of the rainforest causes many of the amphibian species to go extinct. However, some fortunate few figure out how to be less dependent on the water by laying their eggs directly on land. These new creatures, the reptiles, thrive in the arid environment, and explore all of the sufficiently warm landscapes of the new supercontinent. The little lizards diversify as they explore and branch into a host of different species. For the first time, the land is filled with four-legged creatures no longer bound to swamps and streams, bringing about a long and glorious age for the planet.

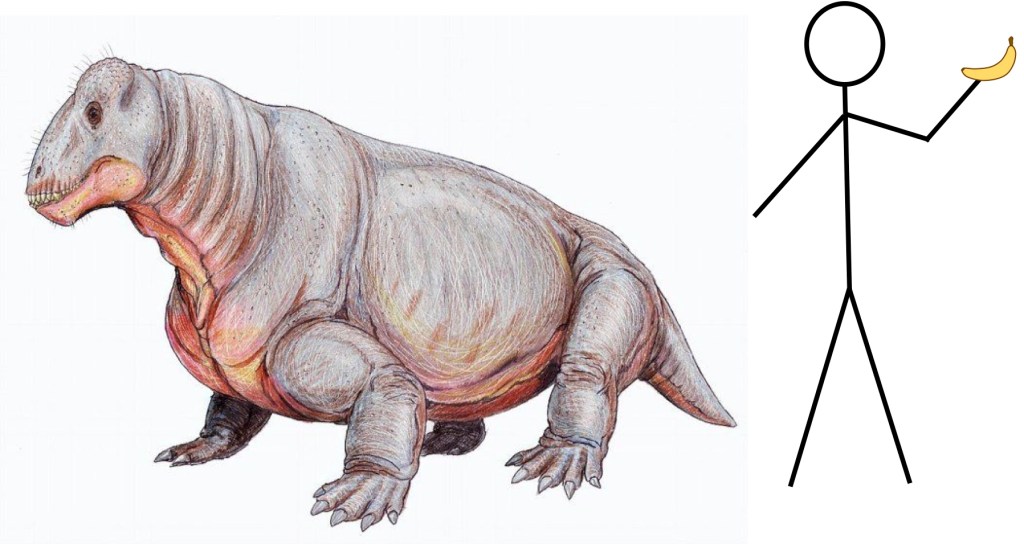

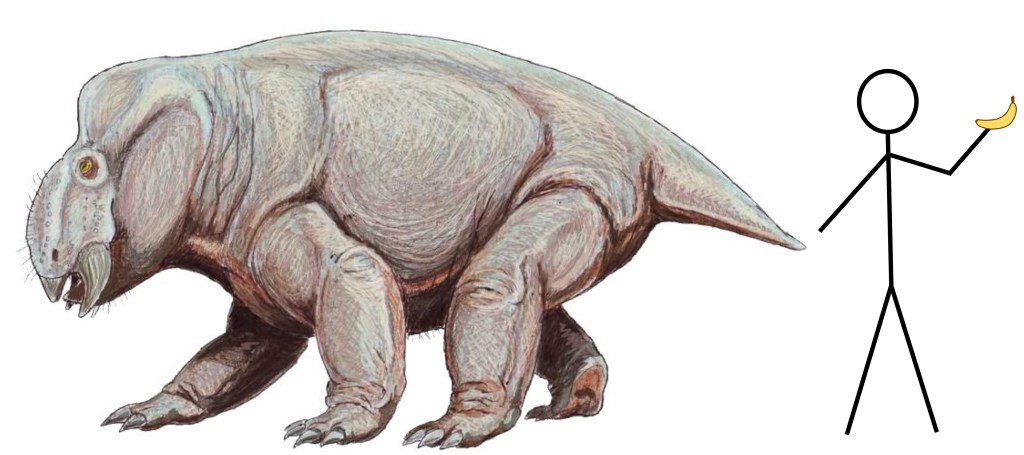

These creatures begin as lizard-like reptiles, but, as they evolve, they diversify to fill many of the roles that modern animals do. Some of them become big barrel-chested herbivores, essentially lizard-cows, others become sleek predators, hunting packs of herbivores like wolves and lions do today.

a cow-sized herbivore

a large predator

This age, called the Permian, lasts for 50 million years before it is abruptly brought to a close. An enormous supervolcano in now Siberia erupts, covering the land to the horizon and beyond (nearly the area of the lower forty-eight United States) with lava and spewing gigatons of toxic gases and ash into the atmosphere. This upheaval of the underworld brings about a cascade of dramatic changes in the chemistry of the atmosphere and ocean causing the world to heat, the ocean to acidify and the balance between bacteria and more complex life to falter. The world shifts faster than life can adapt. The majority of the living things on the planet die, ~70% of life on land and ~90% of life in the ocean. This is the Great Dying, or the End Permian Extinction.

The Triassic

Life is reset. Though most of the large creatures have perished, a few small ones manage to survive.

At the beginning of the triassic, Lystrosauri were by far the most numerous animal on land.

It takes several million years to recover, but the world bounces back with lush vibrance of new kinds. The forests return, and the few surviving tetrapods each give rise to a whole diverse family of descendants. These creatures explore a spectrum of forms from the first small dinosaurs to the first mammals, and most everything in between.

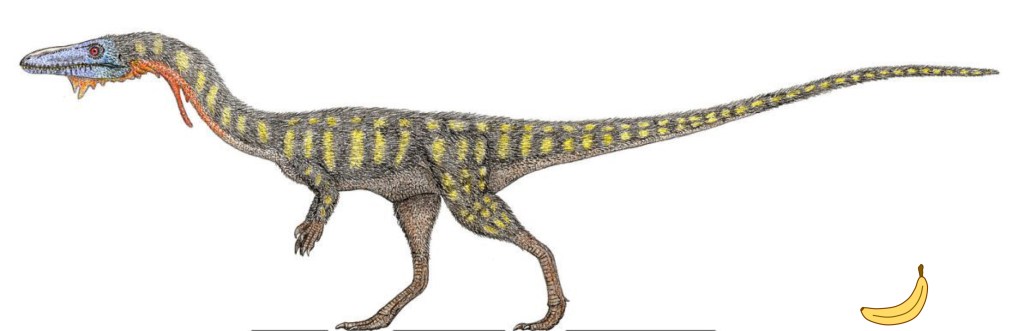

by Jeff Martz

for the Nat’l Park Service

an early mammal relative

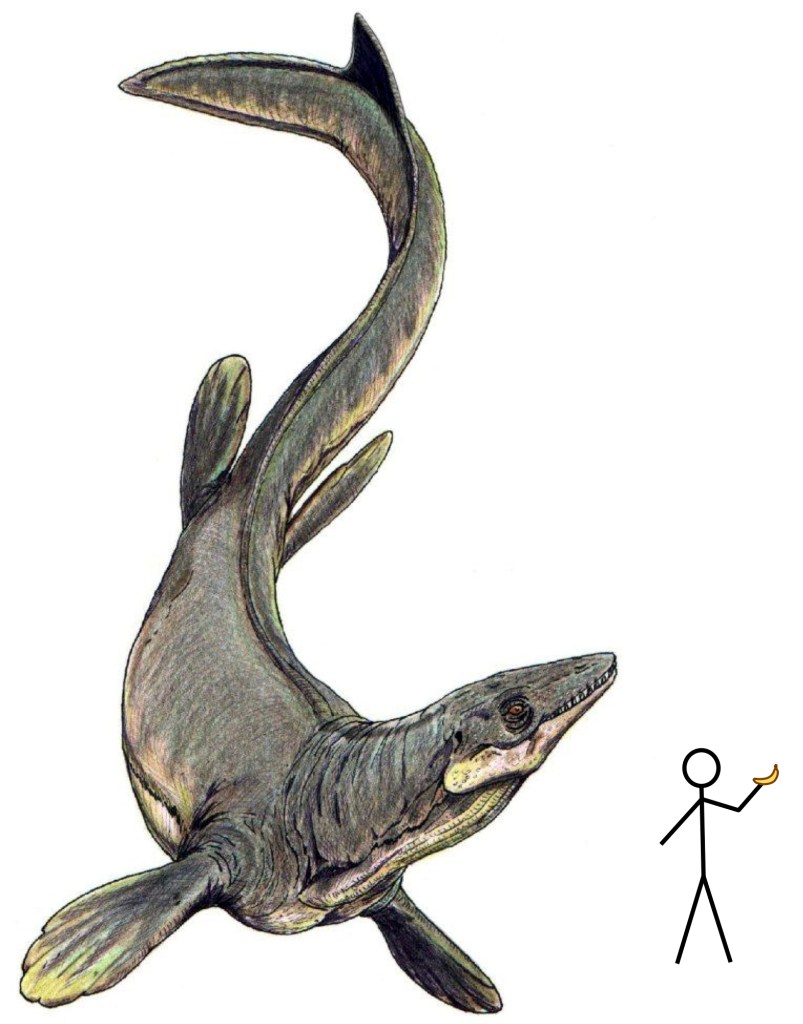

Some coastal creatures take to hunting further and further out in the rich ocean waters, and soon abandon the land entirely. After spending millions of years on the continents, these creatures return to the ocean. Still breathing air, they evolve to be reptilian sea monsters, top predators underneath the waves.

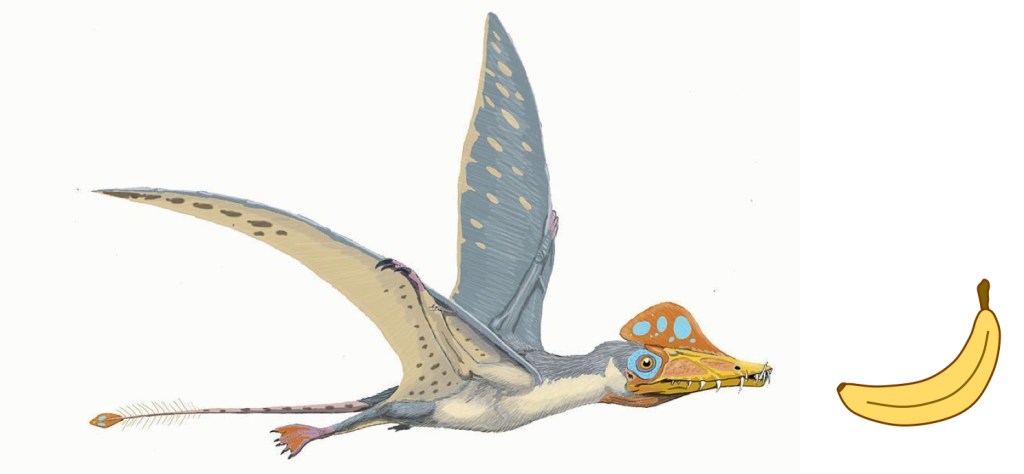

Some animals even take to the air, becoming the second animals to ever do so. They give rise to the pterosaurs, a family of flying beasts somewhere in between birds, bats, and lizards. They live diverse lifestyles, hunting fish, catching insects, or scavenging the corpses of the dead, filling many of the rolls that birds do today.

Scaphognathus[6]

The world reaches new heights of bountiful diversity during the Triassic, until yet another cataclysm brings this era to an end. A different huge volcanic eruption, though not of the same severity as seen at the end of the Permian era, causes many walks of life perish.

Dinosaurs

In the aftermath of the extinction, there’s a scramble for power as creatures race to become the new dominant kind. This time, the dinosaurs take the crown as the new reigning megafauna. They start small as life is still recovering, but the world bounces back into amazing prosperity, which allows these dinosaurs to become absolutely enormous.

A full grown man doesn’t make it to this things shoulder, and it’s twice as long as a school bus!

During this period, the world is exceedingly warm and covered in lush forests and fertile plains. There are even forests growing across Antarctica and fluffy antarctic winter dinosaurs that live in them. Some dinosaurs grow so large that they shape the environments they live in, ripping up trees and leaving huge trails through the jungles and savannas. Other dinosaurs become small feathered things running about on the ground looking for seeds or bugs or lizards.

Besides the dinosaurs, many other animal lineages flourish. The pterosaurs share in the bounty and some also grow to great sizes. One species even grows to have a wingspan closer to that of a small airplane than that of a modern bird.

The largest of the Pterosaurs with a wingspan of nearly 10 meters!

In the oceans, some sea-going reptiles grow to the size true sea monsters.

This era of giants sees the world climb to greater heights of diversity, not only of these large, charismatic creatures, but of organisms of all sizes in all environments. This bountiful period falters as the world suffers a smaller extinction event, but recovers still a world of dinosaurs.

Birds

Velociraptor,

a turkey-sized feathered dinosaur[15]

One species of small tree-dwelling dinosaurs starts using the strategy of leaping out of trees in an attempt to catch bugs or escape from predators. Over time, its ancestors find that growing longer feathers helps them glide from tree to tree. Eventually, their arms develop into proper wings, and the first birds take to the air, becoming the third animal lineage to do so. They quickly master this new ability and soar across oceans, spreading even to the most remote islands around the world.

Flowers

Plants up until this point were dominated by gynosperms, a lovely and diverse group of plants that includes pines, ginkos, and cycads. These plants rely on the wind to carry the pollen of one tree to the seed of the next. They rule the lands in vast forests and scrublands until a revolution occurs in the plant world. Another family develops an intimate relationship with flying insects, recruiting them with sugary bait to carry their pollen. As these plants get better and better at enticing their buzzing counterparts, they evolve more and more elaborately decorated landing strips. Thus, the land blooms for the first time with colorful flowers.

Plants flexible genome allows them to evolve extremely rapidly. These new angiospermes quickly try out all of the strategies their ancestors had before them, becoming weeds, bushes, vines, trees. They even unlock a yet undiscovered ability: Fruit.

Fruits contain tough seeds covered by delicious, nutritious, and often colorful flesh. All of this is an advertisement for long-ranging animals to eat the fruit in exchange for carrying the seeds to far off lands in their gut and leaving them in a pile of nature’s best fertilizer: poop! This second animal relationship allows these stationary plants to travel great distances. They quickly spread across continents and traverse seas.

Like the long age of lizards before, the glorious age of dinosaurs is suddenly brought to an end. A meteorite the size of Mount Everest strikes the Earth with the energy of 100 billion atomic bombs. Like dropping a stone in water, the splash launches a jet in the opposite direction, but, instead of water, it’s a jet of molten rock that gets ejected so far it leaves the atmosphere. The liquid stone rains back down from space creating a shower of tiny meteorites that burn up in the sky. So many rain down that, for a number of days, the whole atmosphere heats up, perhaps getting as hot as a pizza oven. All of the forests of the world burn to the ground, and many creatures fortunate enough to survive the initial hours, die of starvation in the coming weeks. It’s an apocalypse.

Mammals

Out of the ashes, having weathered the storm in underground bunkers, emerge a few families of small mammals: warm, fuzzy creatures that give birth to nearly fully-formed young. Having stayed small and mostly in hiding during the age of the dinosaurs, they flourish in the absence of their giant oppressors. As the forests regrow, the mammals grow with them, stepping up to be the new large creatures of the world.

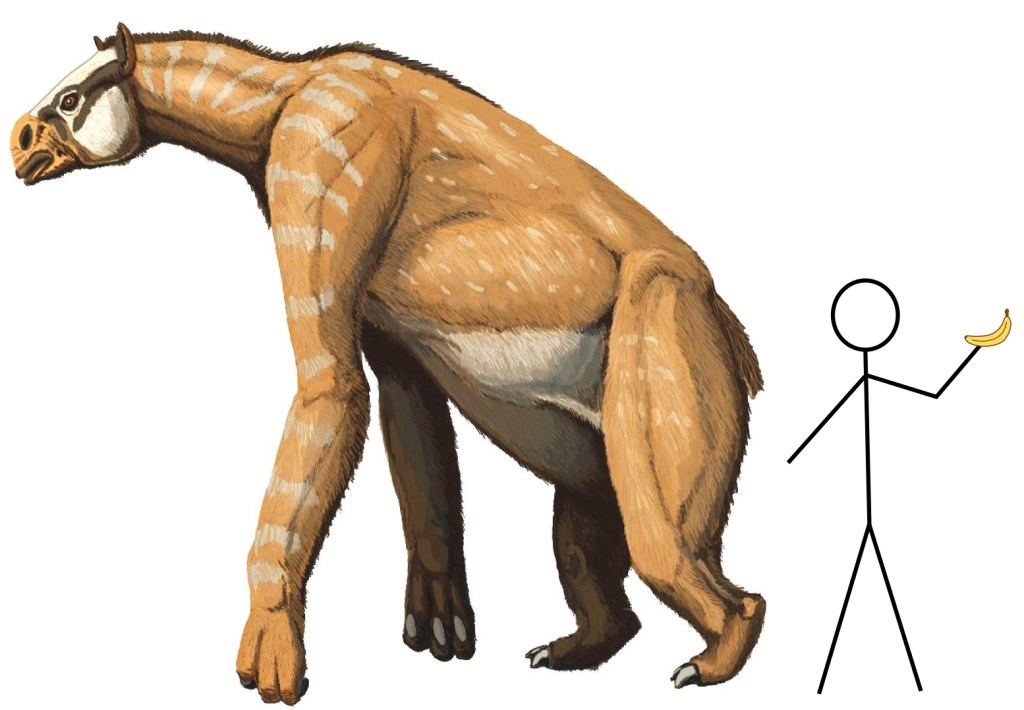

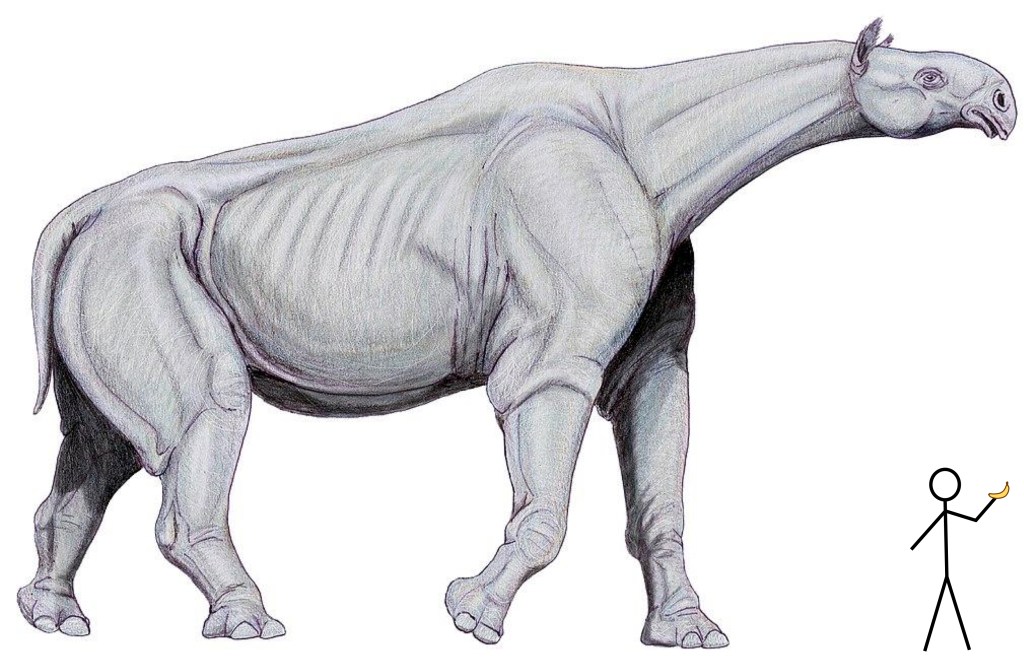

the largest land mammal[6]

The supercontinent Pangea has long drifted apart, and a new collision between the Indian and Asian continents thrusts the Himalaya into the sky. The huge amount of bare rock exposed to the air reacts with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, locking it away and decreasing the greenhouse effect. This causes a long series of ice ages persisting for millions of years.

The forests ebb and grow with the pulsation of the ice ages. Grasslands flourish for the first time, supporting huge herds of mammals that sprawl across continents. In Africa, one family of apes takes to walking in the grasslands as their ancestral forests disappear from under them.

These apes quickly get better at walking, then running across the plains. They hunt and gather in intelligent ways, and evolve larger and larger brains to make sense of the world. In several waves, they travel out of Africa and into Eurasia. They use their adept hands to turn the rocks, bones, and sticks around them into tools. Some lineage’s noises and chatter develop into a structured system of meaning and eventually full-fledged spoken language. This family, our family, wanders into every corner of the world, over frozen tundra and across seas.

Their intelligence allows them to hunt creatures many times their size, and over millennia, the numbers of large creatures slowly diminish. They disappear so slowly that the hunting apes don’t even notice. The only hint is a vague recollection in their elders’ most ancient stories of a more plentiful time of fantastic beasts and endless wilderness.

In a blink of an eye, there are fences and roads everywhere and the wild mammals are nearly gone. Instead, there are 20 billion chickens, 1.5 billion cows, and 8 billion people. The beautifully diverse forests and wild plains have largely disappeared and been replaced with miles and miles of farmland. Monocultures of corn, soy, or oil palms stretch to the horizon. The once wandering apes now live in boxes and stare at magic, glowing rectangles, unaware of the extinction unfolding around them.